NISO Plus is an online conference hosted by the National Information Standards Organization, featuring presenters from all over the world, and from every part of the scholarly communications ecosystem. This is a three-day conference with multiple concurrent sessions spanning time zones and continents. Last week I examined three sessions that looked at various aspects of metadata collection, curation and usage. This second installment looks at three sessions on persistent identifiers (PIDs), covering topics such as the importance of PIDs in the scholarly infrastructure, specialization and governance of PIDs, and national strategies for the use of PIDs.

PID UPDATES – DataCite, RAiD and ROR

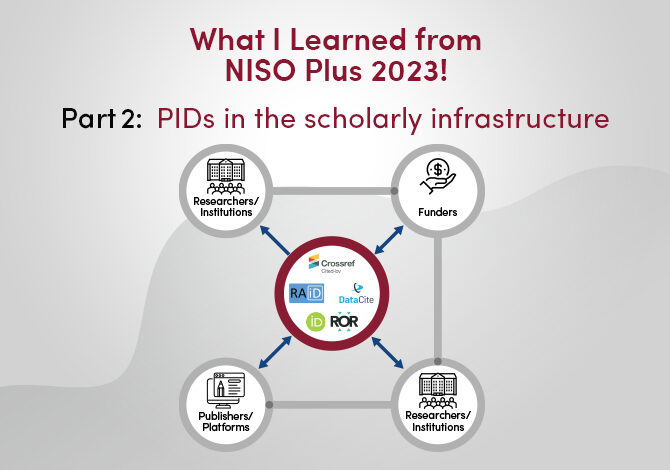

In the introduction to the first session, called “PID Innovations and Developments in Scholarly Infrastructure”, it is pointed out that PIDs uniquely identify scholarly entities, and they connect these entities throughout the scholarly infrastructure for the duration of their existence. It also points out that PIDs are only successful if the scholarly community supports them.

The first presenter, Matt Buys, discussed the DataCite global community approach. DataCite is a non-profit organization that supports data citations and the use of PIDs to improve data accessibility. The community approach advocates for research outputs and resources to be openly available, connected and reusable across disciplines to advance knowledge. DataCite makes research more effective by enabling the creation and management of PIDs, integrating them into different systems, thus facilitating discovery and re-use of research outputs and resources.

To ensure viability within the PID ecosystem there needs to be a sustainable infrastructure, which can be achieved through clear governance by the research community. This governance includes overseeing services that are valuable to community, dissuading the lock down of data so that it is open and reusable, and by making sure the codebase of the infrastructure is open, with common investment by the community. The ultimate goal is to make the research workflow seamless for researchers. This is best done by working within existing workflows rather than trying to create new ones. Buys advocates working with stakeholders and the different PID communities to create common policies that ensure research outputs are discoverable, that the technical staff and the architecture are in place, and that schema changes can be accommodated as they evolve.

The second speaker, Shawn Ross, discussed RAiD, the Research Activity Identifier, and how this PID fits into the research and PID ecosystem. RAiD is developed and managed by the Australian Research Data Commons (ARDC). It is a persistent identifier for research projects and activities. RAiD links organizations, people and outputs to a research project, and consolidates the information about that research project in one place. RaiD has two parts, one is a globally unique PID, and the other is a metadata record that includes some data as well as other PIDs. A RAiD PID will include some basic metadata about the project, such as title, start date and description, and it will include other PIDs (ORCID, ROR, doi’s, etc.) that are related to components of the project. This means a RAiD record creates a web of links to information about the research project or activity, essentially listing disparate elements of a research project and tying them together.

Ross explained why there was a need for a PID for research projects and activities. Research projects are where research happens, especially in disciples with collaborative practices. Projects are a definable and meaningful container. Projects evolve over time and while some PIDs provide snapshots, they don’t provide the bigger picture or trajectory of a research project. RAiD captures this evolution.

Ross also cited the benefits of RAiD. It is a single source of truth, reducing double entry of data, which helps normalize reporting. RAiD allows for a better overview of impact and outcomes of a project over time, and it documents the history and evolution of the project. Finally, RAiD standardizes the identification of projects.

The third presenter, Amanda French, provided an update on ROR, the global, community-led registry of open persistent identifiers for research organizations. Before ROR, there was an incomplete connection among PIDs used for research. For any piece of research, it is useful to know who is involved, what did they study, and where was the work done. ORCID provides the “who”, Crossref and other DOI registries provide the “what”, and now ROR provides the “where”. The purpose of ROR is to make information about research organizations cleaner and easier to exchange between systems.

ROR principles include: Openness, it is openly available to use; Community, governance and scope were developed by the scholarly community, and issues go to a Curation Advisory Board; Sustainability, ROR’s financial model is supported by the operational budgets of the California Digital Library, DataCite and Crossref.

Where is ROR going? French reviewed the ROR roadmap. They are planning a simplification to the metadata schema, which means a rewrite of the schema and the APIs that are used to communicate with ROR. They are planning to improve coverage of research organizations, especially outside North America and Europe. The Funder Registry currently managed by Crossref is being sunsetted in favor of ROR. Finally, they are developing better process for requests for data correction, curation and the addition of new organizations.

HOW MANY PIDS ARE TOO MANY?

Should there be one master vocabulary for persistent identifiers – or should there be many specialized identifiers for different areas, and who should have the authority? In the second session, “One identifier to rule them all? Or not?”, three presenters discuss aspects of this argument.

The first speaker, Gaille Bequet, advocates for preserving diversity in PIDs. She explains the ISO principles of identification: uniqueness (no two resources share an identifier); persistence (including succession plan); granularity (IDs assigned as specifically as possible); stability of kernel metadata (used for minimal identification of a reference, like name, country, etc), access (as open as possible for reuse); scope (definition of the types it is used for); no semantics in PID string (keep it a plain string without meaning); resolution (it should resolve at least to kernel metadata or to the item itself); timing of assignment (assign it as soon as possible, at creation); resilience (linked to persistence, maintain data, track and correct the data); economic sustainability (a business model for ongoing maintenance); and trustworthiness (tied to sustainability).

Bequet points out that an ISSN is a PID, and it is a great example of a good PID, as it conforms to many of the principles described above. Its drawbacks are that it’s not granular, and resolution is limited to metadata, and not to the reference itself. She sees diversity of PIDs as an opportunity. For example, similar PIDs don’t address the exact same needs and there may be shades of difference in their uses. Specialized PIDs might connect to specialized metadata, which might not make sense for a general PID. Bequet says we should foster interoperability between PIDs because there are specialized users and specialized communities, and diverse PIDs contribute to the richness of information that these communities require.

Taking up the theme of interoperability, the second speaker, Jonathan Clark, reviewed why interoperability is so important. Starting in the late 1990’s, when online articles began linking to each other, the problem of broken links rapidly grew. There were different registries that issued DOIs, and the different research communities would go to whichever registry best matched their need. There was a call to action, and now the different DOI registries have learned how to work together. An example of this interconnectedness is ORCID. An ORCID ID is connected to Crossref and DataCite and this means that a researcher’s ORCID record can be automatically updated by Crossref or DataCite.

Crossref pioneered the concept of PID relationships. When metadata contains identifiers referred to in an article, Crossref can capture those relationships and interconnect the pieces of information using the identifiers, which is helpful in enriching the metadata record.

Clark cautions that we need to resist the drive to create new PIDs. He points out that people value new information higher than old information, and this often leads to the development of something new. However, there are legitimate reasons for new PIDs and we are not likely to have one PID to rule them all. What is important is recognizing the role interoperability. We need to have interconnected systems that can understand each other’s PIDs if we want data to work together.

The third speaker, Beth Plale, talked about the role of PIDs in open science, how they can help satisfy funders’ demands, and the danger of a fragmented PID environment. She encourages us to think about the open science ecosystem and how we manage and fund the research objects that have moved beyond the traditional research article (like data sets and software). Institutions, publishers, repositories, content providers, consumers and producers of the research, and PID providers all play a role in ensuring that the open science is findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable (FAIR). This means there needs to be resiliency and stability in the system, which requires money.

Using “FAIR” as a guiding principle, Plale points out that there are IDs for people, organizations, publications and data sets, etc., and that getting all of these linked together is important. Organizations like Crossref and Make Data Count are services that are adding value on top of the other PID services by helping to link things together. Digitally linking a person and a publication and a data set and an award creates the fabric that allows for accessibility and discoverability of the various parts of a research project. These nonprofit organizations are laying the foundation for the linking of scientific work, but they are vulnerable because they have inconsistent or undependable funding.

The OSTP Nelson Memo mandates making publications and supporting data openly accessible if the research is funded by public grants. The guidance to the memo asks that federal funding agencies share metadata about publications and research data, including funding information, and to require the use of persistent identifiers. Plale states that we need interoperability at a lower level because we can’t expect organizations to accommodate multiple PID schemes. This requires an infrastructure that is being created by the non-profit organization like Crossref, DataCite, RAiD, and Make Data Count. Plale feels that the PID infrastructure, which is critical to open science, is underfunded, that a smaller number of stable PID solutions would be more affordable, but that overall, the interoperability of PIDs is a workable solution.

SETTING NATIONAL PID GOALS

The third session on PIDs looks at the development of four national PID strategies, providing useful advice to other nations that want to develop similar policies. The key points brought up by all of the presenters are that national strategies are a collaborative effort, and they require committed, stable funding.

The first speaker, Linda O’Brien, presented “Developing a National PID strategy in Australia”. She talked about the Australian Research Data Commons (ARDC) persistent identifier policy which has been in place since June 2020. She noted that ORCID adoption is high, and that 78% of grant application to the Australian Research council (ARC) include ORCIDs. Adoption of PIDS results in the reduction of administrative burden by $24 million, or by 38,000 person days. This results in an $84 million economy-wide benefit.

O’Brien described a modern data driven approach that the Australian Research Council (ARC) is implementing, which is targeted for completion in 2024. The ARDC has launched a project called Research Link Australia to promote collaboration between industry and universities, and are developing an MVP by the end of 2023. Part of the project is getting industry and researcher organizations to understand the value of PIDS to the research and innovation ecosystem, and to get a commitment to implement a national PID strategy and roadmap from these entities.

The second speaker, John Aspler, from the Canadian Research Knowledge Network (CRKN), discussed the Canadian national PID strategy. CRKN manages two major PID consortia, ORCID Canada and DataCite Canada, and is creating a centralized PID strategy across various systems in the research echo system. The Canadian Persistent Identifier Advisory Committee (CPIAC) also advises both organization on strategy, and are looking at how other PIDs, like ROR, might be included. Aspler also mentioned the Roadmap of Open Science, a government initiative to optimize PID workflows and define a long term national PID strategy.

Aspler points out that the goal of a national PID strategy is to better connect research across different sectors, like universities, government agencies, funders and publishers. Centralized funding has helped to build the Canadian national PID strategy. This funding has reduced the financial burden on the ORCID and DataCite consortia, which lets them do the work to advance the use of PIDs across the research community.

The third speaker, Washington Segundo, from the Brazilian Institute of Information in Science and Technology (IBICT) talked about a technology solution being put in place to aggregate PIDs at a national level. The project and proof of concept is called dDARK, a decentralized blockchain implementation of Archival Resource Key (ARK) persistent identifiers. Segundo described the purpose behind the dARK blockchain proof of concept as a PID hub, bringing together ROR, ORCID, DOIs, ISSN, National IDs, and other PIDs, to ensure their interoperability. This hub facilitates PID assignment to multiple digital objects like articles, data sets, instruments, etc. and for dissemination channels; it helps avoid unconnected PID assignments; it generates open services for publishing dissemination and evaluation; and it preserves metadata through blockchain mechanisms.

Segundo then described the proof of concept as a blockchain siting behind an HTML page that can be imbedded in a journal website or any other system or service. A request to assign or retrieve the appropriate PID for a digital object is made through the website. The response (PID and metadata) is then stored in the blockchain. They are currently testing the system, communicating with the rest of Latin America about using it, studying metadata standards and requirements, and setting up a governance structure. They expect the service to be available by the end of 2023.

The final speaker, Christopher Brown from Jisc, discussed the UK national PID strategy. Jisc has been looking at PIDs for a long time. In 2018, Prof. Adam Tickell provided an independent report to the UK government called Open Access to Research in which he advocated that Jisc collaborate with relevant partners and take the lead on selecting and promoting unique persistent identifiers. The PID roadmap report was written in 2019 and identified 5 priority PIDs as being most relevant to open access: grants (Funder Registry), outputs DOIs (Crossref and DataCite), people (ORCID), organizations (ROR), projects (RAiD). This resulted in the UK PIDs for Open Access project which, from 2019 to 2021, created a roadmap to implement a PID strategy, explore barriers and opportunities, and build community.

The key outputs of the UK PIDs for Open Access project include building a business case for investment in a UK PID strategy, and creating a PID support network (PSN) to lower barriers and costs of PID adoption. The Independent Review of Research Bureaucracy report in 2022 endorsed a proposal for a PID support network, and recommended extending the model throughout other digital research platforms.

The Research Identifier National Coordinating Committee (RINCC) was set up to create a governance and financial structure. It brings stakeholders from across the community to provide strategy and shape priorities, focusing on PID-related activities and policies in the UK. A cost-benefits analysis showed that 55,000 person days (at a cost of 19 million pounds) was wasted rekeying metadata in UK institutions, and that a coordinated PID strategy would save an estimated 45 million pounds over 5 years.

Brown also reviewed the work of the National PID Strategies Working Group, a project led by the Research Data Alliance, which attempts to align different national PID strategies by mapping common activities across national agencies. This working group is producing guidance for developing national PID strategies that work across boundaries, and a how-to guide for PID strategies are still emerging. Brown concluded by warning that PID strategies are a snapshot in time and need to be revisited occasionally; and that though there are many similarities between different PID initiatives, there are also many differences.

In my next installment of “What I Learned from NISO Plus!” I will summarize what I learned from a collection of sessions on open access usage reporting. Those sessions include, “Understanding the value of open-access usage information” and “Understanding stakeholder needs and advancing trust through shared infrastructure”.

By Tony Alves