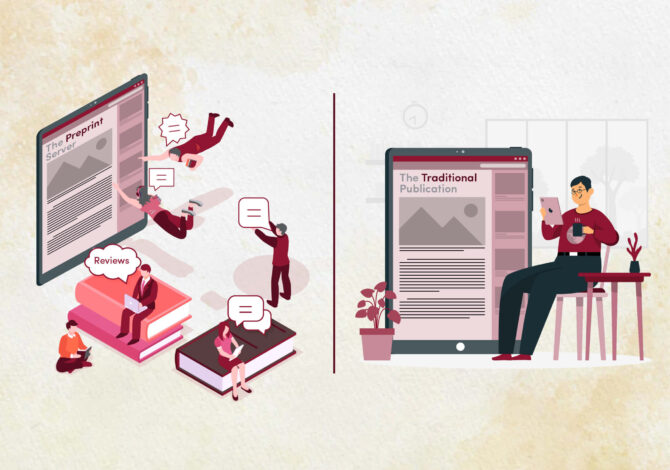

A key difference between a preprint and a published article is that the published article has usually gone through a traditional peer-review process where experts in the form of editors and reviewers evaluate the research and the authors revise the paper based on the reviewers’ suggestions. Some people feel that preprints lack quality because they have not been through this formal peer-review process. It is true that preprints do not go through traditional peer-review, though some preprint servers do employ a screening process before posting a research paper. Recent studies examine the differences between a preprint and the published version of the article. These studies have shown relatively little change between the two versions of the research.

In a study posted in PLOS Biology on February 1, a research team investigated how preprints change upon publication by comparing abstracts, authorship, and figures and tables of bioRxiv and medRxiv preprints with their published versions.

Method: To come up with an equal ratio of bioRxiv: medRxiv preprints, the team identified 105 COVID-19 preprints posted between January and April of 2020, and 105 non-COVID-19 preprints posted between September 2019 and April 2020 that were subsequently published in respective peer-review journals. The team narrowed the total to 184 preprint-published study pairs.

Findings: The study concluded that preprints were often published with minor changes made to the conclusions in the abstracts of their published version by increasing sample sizes or statistics. Only 17.2 percent of COVID-19-related abstracts and 7.2% of non-COVID-19-related abstracts had major alterations. The figures and tables experienced fewer changes, meaning there was a limited need for new experiments. Moreover, the majority (>85%) of preprints had no changes in authorship when published. Interestingly, none of the published bioRxiv preprints had any authors added or removed from the corresponding author lists. Overall, it concludes that, for most preprints, there is little need for additions or alterations before final publication.

PLOS Biology also recently published a study, originally available on bioRxiv, examining how peer review changes the text of preprints in bioRxiv. This study aimed to compare the language (linguistic features) contained within the bioRxiv preprints with their corresponding published articles by using computer programs. Note that the study focused on the textual analysis of bioRxiv preprints versus peer-reviewed counterparts and not evaluating results and conclusions.

Method: To compare texts, the researchers identified bioRxiv preprints linked to their published versions in PubMed Central’s Open Access (PMCOA) corpus. They also used the New York Times Annotated Corpus (NYTAC) as a negative control to evaluate the textual similarity between bioRxiv and PMCOA compared with nonlife science text. They downloaded a snapshot of bioRxiv corpus on February 3, 2020, a snapshot of PMCOA corpus on January 31, 2020, as well as a snapshot of NYTAC corpus on July 7, 2020. They found 17,952 preprints-published pairs.

Findings: The study concluded that over 77 percent of bioRxiv preprints were successfully linked within the PMCOA corpus, suggesting that COVID-19 preprints are more likely to be published. Posted preprints had no alteration when published except for a few typesetting and additional supporting items. Moreover, they found the COVID-19 preprint’s time to publication was faster than non-COVID-19 preprints. It is the same conclusion the Springer Nature Group concluded in its study posted on January 31.

To link bioRxiv and medRxiv preprints with their published counterparts in PMCOA, the team created a web app, Preprint Similarity Search. Using machine learning, the tool maps around 2.3 million PubMed Central open access documents. This helps bioRxiv and medRxiv users find journals or articles that are most linguistically similar to their preprints, which potentially takes them to most relevant journals to submit their preprint for peer review and publication.

It seems that in general, preprints are fairly comparable to their peer-reviewed counterparts. The Preprint Ecosystem is vast and offers a significant opportunity to researchers and publishers willing to engage with many existing and emerging services. Our community expounded upon these available services in a recent webinar featuring representatives from across preprint servers and related integrated services.

Having read this, where do you see the Preprint Ecosystem heading? Share your thoughts here.